[ad_1]

Reimagining Kerala: Unleashing Economic Potential Beyond Mall Culture

Kerala, long considered a bastion of communism in India, presents a complex narrative of evolving ideologies, vested interests, and youth aspirations. While classical Marxism and Socialism are found to be dwindling, particularly among the younger generation, the state grapples with its communist legacy and the remnants of the Nehruvian socialist era. Funding for many of the state-promoted undertakings often seems to prioritize salaries over necessary public services, creating an environment reminiscent of a “command economy” rather than a demand-driven market economy. This environment fosters fear and hesitation within the private sector due to “rent-seeking” behaviour by leading political entities.

Kerala’s still sizable public sector bears some resemblance to the command economies of East and Central Europe. While the CPI(M) is ideologically aligned with Chinese communist parties, the Kerala model of socialism is built on party-led cooperative organizations across various segments. Here, communists are not alone; substantial Nehruvian Socialists, currently represented by the Indian National Congress led by V.D Satheeshan, coexist. Nehruvians advocate for India to be managed as a socialist state, with a strong role for politicians, spacious cabins not only for themselves but also for their supporting staff, and significant power to flex their political muscles.

Kerala’s society is shaped by several ideologies and interest groups. While the traditional Marxist ideology is losing its grip, particularly among the younger generation, even the CPI(M) and its leaders increasingly look to China’s market-driven communist model for inspiration, attracted by its more conducive environment. In contrast, some old-guard Nehruvian Congress groups yearn for a return to the restrictive environment of the pre-1991 Nehru-Indira era. This tension often goes unnoticed, yet it has significant consequences. For example, the recent campaign against a textile manufacturer spearheaded by a prominent UDF-Congress leader ultimately led the company to relocate to Andhra-Telangana. While trade unionism presents challenges, managing labor and unions is far less daunting than facing systematic and targeted attempts to kill industries and jobs, regardless of the underlying motives.

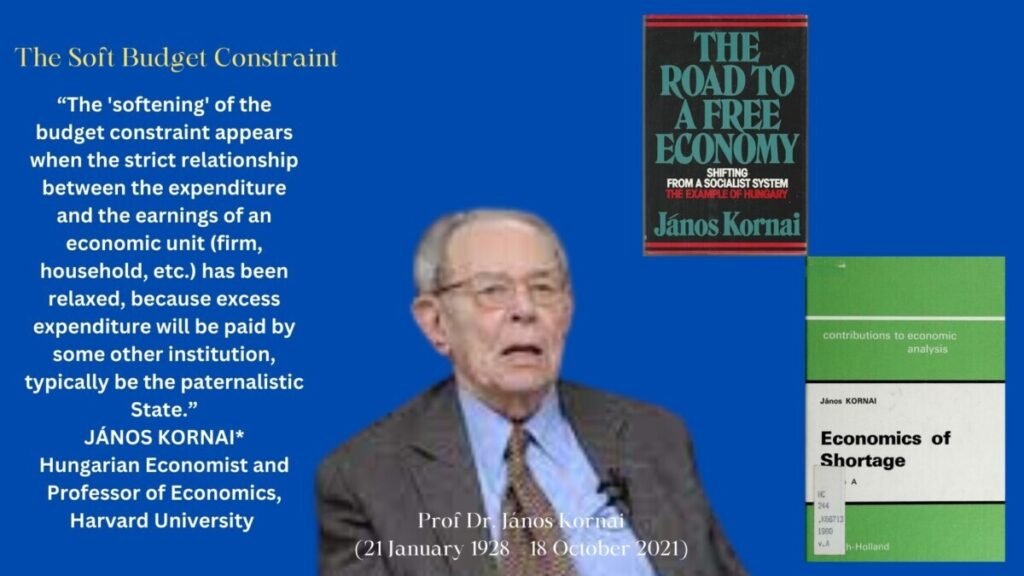

Soft Budget Constraint vs Hard Budget Constraint

Kerala’s economy showcases features typical of a former communist system. Janos Kornai, a Hungarian economist and Harvard Professor, coined the term “soft-budget constraint” in his book “Economics of Shortage” (1980). This term aptly captures how state-owned enterprises in communist states relied on government subsidies and support, regardless of their financial losses, to remain operational. In contrast, a “hard-budget constraint” signifies stricter controls on spending. Entities in a market economy, including the state itself, are accountable and operate under stringent fiscal discipline. This ensures responsible financial management and avoids the pitfalls of excessive spending observed in communist economies.

.Economic Landscape and Soft Budget Constraints

Kerala’s economic landscape demonstrates traits similar to those found in former communist states. This lack of a hard-budget constraint hinders efficient resource allocation and economic growth, emphasizing the importance of fiscal discipline for sustainable development.

The economic landscape in Kerala operates under a soft-budget constraint akin to former communist East and Central European economies. Additionally, challenges arise from bureaucratic reluctance to align with the broader national economic agenda. While ideological foundation erodes, exemplified by the emergence of entrepreneurs like Veena Vijayan, daughter of Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan, the reformist endeavours in the State face formidable challenges from entrenched interest groups and internal party resistance.

The state’s reliance on borrowing, even for basic expenses, sets it apart from other Indian states. Moreover, its extensive network of state-supported and promoted undertakings bears a striking resemblance to the command economies of the former Eastern European communist bloc.

A former Kerala finance minister infamously suggested simply printing money to clear the state’s massive debt (exceeding one lakh crore) and fund various expenditures, including salaries, pensions, new posts, and even foreign travels. While the dominant socialist ideology is losing its hold, particularly among younger generations, Kerala has witnessed a surge in entrepreneurial aspirations, evidenced by the rise of numerous startup firms. However, individuals who don’t find their niche within the startup ecosystem often resort to migration or seeking opportunities elsewhere.

Resistance to Change and Reforms

While ideological resistance to a free-market agenda weakens, a more significant challenge arises from the intricate network of vested interests. This situation parallels the late 1980s in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, where the ideological foundation of communism crumbled, yet the system remained entrenched due to powerful networks of interest groups. Beyond the formal economic structure, a web of stakeholder groups exerts a significant influence on Kerala’s economic trajectory. These include:

- Elites: A privileged group comprising legislators, bureaucrats, employees of state-backed enterprises, and individuals benefiting from government grants and aid. They maintain strong ties with political parties, often utilizing these connections to gain concessions and subvert regulations.

- Organized Businesses: Certain corporate entities leverage their political connections to acquire land deals, bypass regulations, and gain monopoly control over the Kerala market.

- Intelligentsia, Think-tanks, and Cultural and Literary Leaders: These groups provide intellectual and thought leadership, forming the foundation for the entire system.

- State-funded Institutions, Government-aided Service Industries, and Non-Profit Community Groups: These function as closed networks where salaries are paid from the public exchequer, further perpetuating the soft-budget constraint system.

This network of stakeholders, comprising elites, organized businesses, and the intelligentsia, maintains close ties with political parties, perpetuating the existing system and resisting change. From literary groups to academies and think tank NGOs, all are part of this network. Political patronage from both the LDF and UDF fronts ensures the continuation of the current political arrangement in the state. Funding, hosting, and supporting the activities of such groups, both within Kerala and Delhi, comes at a heavy cost, leading to the erosion of public resources.

Challenges and Aspirations:

While the socialist ideology wanes, entrepreneurial aspirations rise, evident in the burgeoning startup ecosystem. However, two significant challenges remain: the entrenched remnants of Nehruvian socialism and the fierce resistance from vested interest groups.

For the youth, breaking this stalemate is crucial if they desire a future beyond migration or low-wage jobs in sprawling shopping malls across Kerala’s major cities. Ironically, the rise of these malls has simultaneously stifled the potential of smaller businesses catering to local consumers and aspiring to expand globally through e-commerce supply chains. The State’s policy of promoting large retail malls and sale of cheap goods from global manufacturing hubs in those malls effectively drives the final nails into the coffins of Kerala’s entrepreneurs.

Conclusion:

Kerala stands at a crossroads. A weakened ideological base coupled with rising youth aspirations presents a unique opportunity for change. Addressing vested interests and implementing comprehensive reforms hold the key to unlocking Kerala’s economic potential and creating a thriving future. The youth must champion this transformation, and Kerala must embrace economic liberalism to drive innovation and growth.

(P. Koshy)

8 December 2023

[ad_2]

Source link